SST: A Dream Unfulfilled

Sixty Years Ago, It Seemed Like a Sure Thing. (No. 80)

On a cold February night in 1977, I sat down in front of the family television for a Friday evening of mindless entertainment, and boy, did I get it. The ABC Movie of the Week, SST: Death Flight, remains memorable today only because it was so spectacularly, unintentionally awful.

Following the blueprint of 1970s disaster epics like Airport and The Poseidon Adventure, the film featured a revolving door of well-known—if mostly past-their-prime—actors. The cockpit was manned by Bert Convy and Peter Graves, while the passenger cabin was a bizarre “Who’s Who” of television royalty, including Tina Louise, Burgess Meredith, and even Billy Crystal in an early role.

The plot speculates what the maiden voyage of America’s first Supersonic Transport (SST) might have looked like if it had been beset by every trope in the screenwriter’s handbook. Clunky subplots involving strained romances and professional rivalries filled the first hour. A disgruntled employee tampers with the hydraulic system, ensuring the flight would be anything but smooth. And in a weirdly high-stakes twist, a passenger inadvertently brings a deadly, experimental strain of influenza on board.

The film eventually devolves into a desperate race against time as the plane, leaking hydraulic fluid and carrying a plague, is refused landing rights at every airport in Europe. Not quite grounded enough to be taken seriously, nor campy enough to be “so bad it’s good,” the film landed (so to speak) in a purgatory of silliness.

Perhaps the most bizarre aspect of the film, though, was its timing. By 1977, the dream of an American-made SST had been dead for nearly a decade. The Boeing 2707 project had been defunded by Congress years earlier, in 1971, a casualty of skyrocketing fuel costs and environmental protests regarding the sonic booms that would shatter windows and nerves below. Watching the movie felt like seeing a futuristic vision of a tomorrow that had already been cancelled.

The idea of a commercial supersonic transport was first proposed in the 1950s, just a few years after Chuck Yeager broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1 in 1947. The concept was immensely appealing to a world captivated by speed. A plane traveling at Mach 2—twice the speed of sound—could fly from New York to Los Angeles in just two hours. At Mach 3, the flight from Los Angeles to the new state of Hawaii would have been less than 2 hours.

By the 1960s, the race to build the first SST became a matter of intense national pride and economic strategy, resulting in three primary competitors: England/France, the Soviet Union, and the United States.

The most successful of the SST designs, the Concorde, was a joint venture between British BAC and French Sud Aviation. Its iconic delta wing and “droop-nose” allowed it to maintain stability at both low landing speeds and supersonic cruise. It entered service in 1976 and became the gold standard for luxury travel, though it was limited by its high operating costs and small passenger capacity of about 100 people.

Dubbed “Concordski” due to its striking resemblance to its Western rival, the Tu-144 actually beat the Concorde to the first supersonic flight by two months. However, it was plagued by technical issues. To achieve lift at low speeds, it featured unique “canards”—small wings behind the cockpit—that retracted during flight. The Soviet government cancelled the project after a fiery, high-profile crash at the 1973 Paris Air Show.

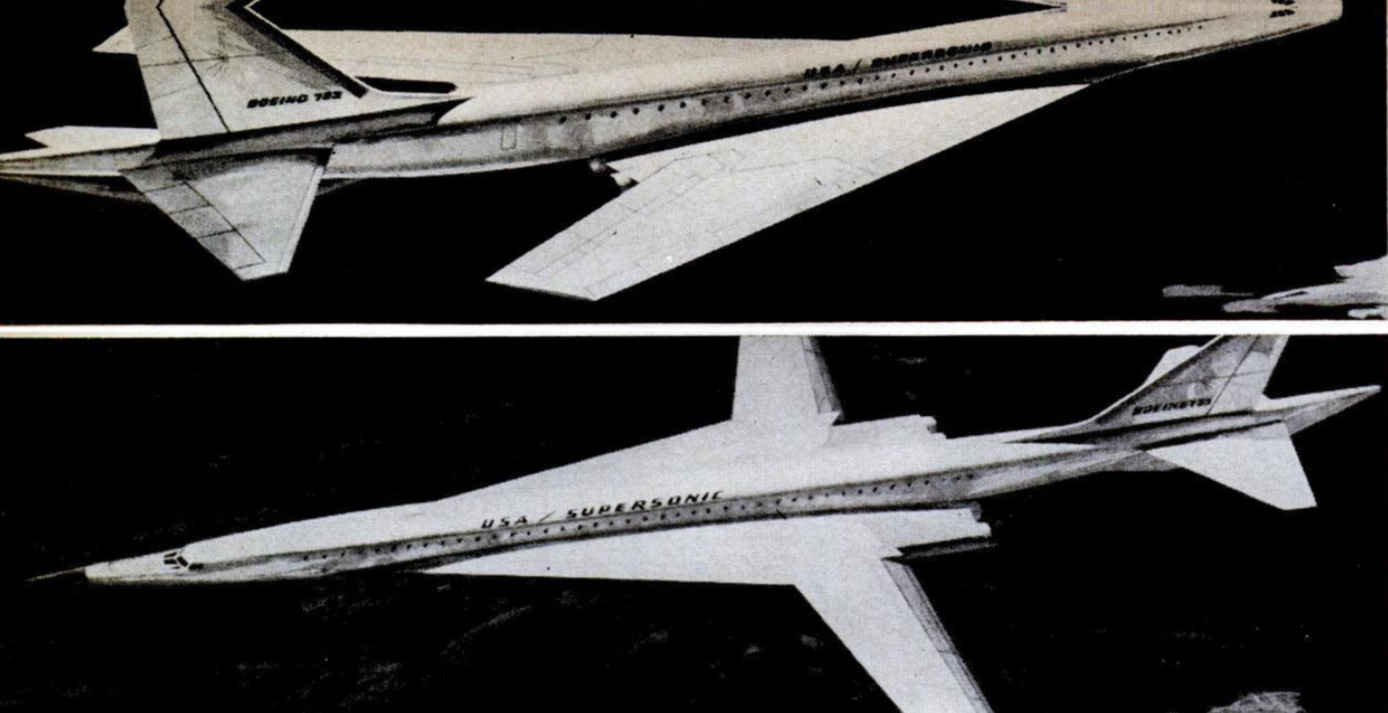

The American entry—the one depicted in the movie—was intended to be the “Concorde Killer.” It was designed to be much larger, carrying nearly 300 passengers, and faster. Most notably, Boeing originally proposed a “swing-wing” design, similar to that of the F-14 fighter jet, where the wings would move forward for takeoff and sweep back for high-speed flight. This 1966 Popular Mechanics article provides a (very optimistic) glimpse into the technology.

In reality, though, the American SST was undone by its own ambition. The “swing-wing” mechanism proved too heavy and complex, forcing Boeing to pivot to a fixed-wing design, and an absurd amount of fuel was required to achieve the goal of Mach 3. By the time the government pulled funding, the “environmental boom” had become a political lightning rod. Critics argued that the sonic boom was an unacceptable “sound tax” on the public, and concerns grew that a fleet of SSTs might damage the ozone layer.

When SST: Death Flight aired in 1977, American supersonic travel was already long dead, leaving the Concorde to command the skies alone for the next 27 years, until its own fiery Paris crash grounded it in 2000. In recent years, advances in engine and materials technology have revived the idea of commercial faster-than-sound commercial travel. Boom Supersonic, an aircraft manufacturer based here in North Carolina, has successfully tested a 70-passenger jet that flies at Mach 1.7, and hopes to have it in commercial service by 2029. Modern tech like the internet and satellite phones have already shrunk the globe in ways unimaginable in 1977. Perhaps it’s time to revisit planes that get us there in half the time.